Marjorie Montagu lived in South Ealing during the Great War, in which all three of her sons fought on the battlefields of the Somme – with dramatic results in each case.

The Montagu family moved to Ealing sometime in the first decade of the twentieth century. In the 1901 Census, Marjorie is listed (as Margaret) with her daughter Irene and three sons living in Shepherd’s Bush (where the children were all born), having herself been born in Hampstead in December 1863. She is listed as married but her husband Arthur does not appear in either the 1901 or 1911 censuses; they appear to have married in around 1893 but I haven’t been able to track down the event or anything of her life before then.

The Montagu family in 1911

In 1911, the five were living at 28 Overdale Road in Ealing, and by 1914 they had moved just around the corner to 47 Devonshire Road. Then came the Great War…

The oldest of the three boys was Eric and he was the first to volunteer. In November 1914 he volunteered for 9th battalion of the Rifle Brigade. Within a month, however, they decided that he was not fit for active service and he was discharged under provisions in King’s Regulations that allowed men to be rejected within three months of joining up.

As the war dragged on past 12 months, Eric apparently became acceptable to the army – whether through improvement in his physique or through lowered standards is not clear – and he joined the 30th (Reserve) battalion of the Royal Fusiliers on 18 September 1915. In November, he was transferred to the 24th Battalion (the 2nd Sportsmen’s), and was sent to the Western Front to serve with them. The battalion joined the 2nd Division in late 1915.

The middle brother, Graham, joined the King’s Royal Rifle Corps in November 1915 (during the Derby Scheme period), aged 18. Like Eric, his enlistment papers record his employment as ‘clerk’. After four months training with the 15th (Reserve) Battalion, he was sent to the 12th Battalion in March 1916. As part in the 60th Brigade, in the 20th (Light) Division, the battalion was on the Somme battlefield in August 1916. After five days under bivouacs, the battalion went into the trenches at Guillemont on 27 August. The battalion war diary tells us that they were in the trenches until the 30th, during which time they were bombarded and fought off two German attacks. During that period in the trenches, Graham Montague was killed in action – on 28 August.

He has no known grave and is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing, although with a slightly different date of date to that in other records. (This is the only record I could find the name of their father, Arthur, who is listed as being deceased)

Battle of Guillemont. 3-6 September 1916. Stretcher bearers and dressing station at Guillemont. Copyright: © IWM (Q 4221)

A few months later, Eric was at Mailly-Maillet, some 30 miles from Guillemont. What happened to him was syndicated across many papers in December 1916 – the fullest account, unsurprisingly, comes from the local paper, the Ealing Gazette and West Middlesex Observer, which told the tale with gusto:

Private Eric Montague [sic], Royal Fusiliers, the eldest son of Mrs Montague, of 47, Devonshire-road, South Ealing, is among the eight hundred patients at Mile End Military Hospital. He has returned from France minus his right arm, and deserves to figure at the very top of the list of local heroes, since on his own initiative, and utterly regardless of personal danger, he undertook the severance of the limb, and by so doing made possible the rescue of two of his comrades, whose position at the time was extremely critical.[…]

“One of the bravest and coolest men I have ever met,” is the Captain and Adjutant’s description of our gallant hero […] after referring to the pluck and conspicuous bravery displayed by him in the performance of one of the most noteworthy deeds – a deed thoroughly deserving of the award of the Victoria Cross.

The story is a thrilling one. October 24th found Private Montague, along with others, in a dug-out captured from the Germans. It was supposed to be bomb-proof, but heavy shelling by the enemy soon proved the contrary, and Private Montague and those with him had to recognise they were in “a tight corner.” Escape, of course, as impossible. The enemy’s deadly fire meant the dug-out’s total destruction; and Private Montague became wedged in by the debris, and two of his comrades were buried with him. To extricate him seemed like attempting the impossible, and was rendered the more difficult through his right arm being pinned down by a large tree. But coolness and bravery exerted itself, and found Private Montague equal to the occasion. With the cries in his ears for assistance on the part of the two “Tommies” buried beneath him, he never wavered in his determination to free himself if possible, and thus endeavour to make the way clear for their rescue.

There was only one way out – his right arm must go! A moment later he had brought his knife into play, and was hacking away at the limb. There was no time to be lost, and this apparently was his only fear, since he found the instrument not sharp enough. Fortunately a doctor was at hand with a much sharper blade, which was passed down to Private Montague, and the terrible operation was completed. Displaying courage and endurance remarkable to witness, he was happily got out alive, and by his self-sacrifice the other two men were also brought to safety – one found to be suffering from shell-shock and the other having a fractured thigh.

The letter to Marjorie from the adjutant (possibly Cecil Palmer Harvey, a former student at the University of London), is quoted at length:

“He has been working under me for the last two months, and has always done his work extremely well, showing keenness and a desire to help to the utmost of his ability. He is a great loss to me, and his place will be difficult to fill. I am sure it will be a pleasure to you when I tell you that he was one of the bravest and coolest men I have ever met. He displayed the most remarkable courage and endurance during the time that he was wedged in by the debris of the dug-out, and I really thank God that we managed to extricate him alive.”

From this and the war diary, it looks as though Eric was in the headquarters dug-out, which was apparently shelled on the afternoon of the 24th and “throughout the day” on the 25th. Montague is recorded as being wounded on the 25th, along with four other men – perhaps two of them were those men trapped with Eric in the dug-out, whom his bravery helped to save. (L/Cpl T Ryder, and Privates EE Keeley, FA Holingworth and A R Evans).

The details of the event are quite striking. The day-long shelling to destroy a ‘bomb-proof’ dug-out; Eric being trapped in a way that somehow blocked the rescue of those two comrades; that the situation apparently meant that the doctor was not able to reach Eric to perform the amputation; the sheer horror and bravery of having to cut off ones own arm to save two comrades.

Captain Harvey hinted to Marjorie that some form of gallantry award was possible – and the Gazette clearly agreed. The Commander of 2nd Division, writing to Eric directly, played down that possibility but said “I should like you to know that your gallant action is recognised, and how greatly it is appreciated.”

Account of Montague’s injury from Daily Mirror 6 Dec 1916

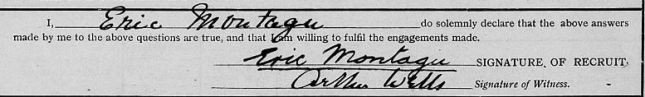

Eric’s army service papers show one impact of his amputation: the change in his handwriting and signature:

Montague’s signature on enlistment in 1915

Montague’s signature on demobilisation from the army

In July 1917, nine months after his treatment at Mile End, Eric went to Roehampton to be fitted with an artificial arm. On leaving the army that Summer, he was given a pension of 27 shillings and 6 pence a week for an initial 9 weeks, followed by 19s 3d per week for life. He appears to have lived most of his life with his mother. In the 1939 Register they are listed together at 47 Devonshire Road; he is recorded as being a senior clerk for a scientific instrument maker. His sister, Irene, had left Ealing some time earlier and had died in 1923 while living on Westbourne Terrace near Paddington Station.

Beresford Montagu, the youngest son born in December 1898, served in the Royal Field Artillery. It’s not clear when he joined the army but he may have done so underage. Although only 12 in April 1911, he was apparently serving in the RFA in 1916 when he became a member of the Simplifyd Speling Sosyeti (as recorded in their journal The Pyoneer ov simplifyed speling – which Archive.org has some trouble transcribing accurately!).

By late 1918, he was a lance bombardier (equivalent to a lance corporal in the infantry), serving with A battery, 86th (Army) Brigade. In September he was – like his brothers at the defining moments of their war experience – serving on the Somme battlefield at Ronssoy (about 30 miles East of Guillemont where his brother died two years earlier). On 29 September, his artillery brigade were supporting the 27th American Division in their attack on the German line between Nouroy and Gouy, between St Quentin and Cambrai, as part of a more general push to break the Hindenburg Line. The brigade war diary records the successful actions of the day and concludes, “Batteries suffered severe casualties from [Machine Gun] and shell fire.”

His actions under that intense fire earned Beresford the Distinguished Conduct Medal. In the words of the London Gazette:

For fine courage and devotion to duty on 29th September, 1918, at Ronssoy, under intense enemy shelling. When the No. 1 was wounded he took over his gun. Twice the remainder of the detachment became casualties, but he maintained his gun in action in spite of being wounded himself. He refused to be taken away until the barrage was finished.

Like Eric, Beresford Montagu survived his experiences on the Somme and returned to Ealing. He married a Lilian Cox in 1925 and moved frequently between the UK and the USA in the 1920, recorded variously as a valet, a chauffeur and a motor mechanic, with 47 Devonshire Road given as his UK address. By the Second World War, he was living on Pheonix Avenue, Elmira, in up-state New York; his US Army draft card records him as working for the Merchants Acceptance Corp in the same town. He died there in 1964.

Beresford had outlived his mother by 8 years, she died in 1956. Eric lived at 47 Devonshire Road until his death in July 1970 more than 50 years after his and his brothers’ experiences on the Somme during the Great War.

Sources:

- Ancestry records – various military and census

- National Archives – war diaries (currently free to download)

- Ealing Gazette and West Middlesex Observer (on British Newspaper Archive)

- History of the 27th American Division (pdf)