The Great War had a global impact, but it was experienced my millions of individuals, families and communities across the world. By focussing on one street in South London, we can see something of the variety of war experiences.

In 1918, all men aged 21 or over and servicemen aged 19 or over were eligible to vote. The register for that year therefore lists (or should list) every man on military service in July 1918, when the register was compiled. Those who were absent on military service were marked with a lower-case ‘a’ next to their name and NM in the ‘qualification’ column (as opposed to HO for home owner and R for resident). Unfortunately, the more restrictive franchise for women means that very few female service personnel are listed.

Some boroughs published separate registers listing the military details of those men on war service. Lewisham was one of these boroughs and I have picked Arthurdon Road in Ladywell. The road is opposite the Ladywell entrance to Brockley and Ladywell Cemetery, part of a series of roads with odd names: Phoebeth, Francemary, Maybuth. They were built around the turn of the century (the streets south of Ladywell road are not on the famous and fascinating Booth Poverty maps), so the people living there in the 1910s must have been among the first to occupy Arthurdon Road.

1930s map of Ladywell showing Arthurdon Road – from ideal-homes.org.uk

There were 148 voters for parliamentary elections registered in Arthurdon Road in 1918 (the local franchise was different, but the general election register is the key one for our purposes). Thirty one men were listed as absent on war service, or 21 %. These were men away on military service aged 19 or older (civilian voters were men over 21, and women over 30 with a property qualification – there were some women on the absent registers but not many, and none on Arthurdon Road).

These servicemen of Arthurdon Road were 31 of the 17,589 absent in Lewisham borough, which was smaller then than today with 81,220 voters, meaning that 31.6% were absent on military service. Across London 433,800 were registered absent of 1.96 million voters (male and female), or 22.1%.

Arthurdon Road today(from googlestreetview)

Going along house by house, these are the men who were listed as absent voters in 1918:

Odds

1 – At the top of the street were the Youngs brothers, both of them confirmed war heroes:

- Harold William Youngs was born in 1889 and married Violet Lillian Bellsham in 1911; their daughter Betty was born in 1913. In January 1917, he joined the Royal Flying Corps and in April he went out to France. In June 1918, he is noted as moving from 16th Balloon Company to 24 Squadron, but he appears later to have returned to ballooning. Sadly, he then died in March 1919 in France, serving with 14th Balloon Section; his death was officially attributed to his own negligence. This did not, however, stop the authorities from awarding him the Military Medal in July 1919. The medal was awarded for bravery in action, but sadly no citation explaining what he had done was published.

- Arthur Leslie Youngs was two years younger than his brother. He joined up first, though, joining the Royal Army Medical Corps on 1 September 1914, leaving his job as a schoolmaster in Tottenham. He went to the Western Front in May 1915 with the 4th London Field Ambulance and remained there for nearly three years. In August 1916, he was awarded the Military Medal (three years ahead of his ill-fated older brother). He did not get through unscathed, however. On 8 April 1918, he was wounded in the right leg. His medical report states “Bricks from a house fell on him and bruised his right side. Was sea sick coming across [back to the UK] and brought up some blood. States he got some gas several days previously. Piece of metal taken from knee in France”. An x-ray showed there was still shrapnel in his leg. He was eventually discharged in March 1919.

3 – Their neighbour George Douglas Sylvester was a tea buyer born in Brighton in 1884, who lived with his mother and stepfather (in 1911 he was in nearby Tresillian Road). He joined the Royal Naval Air Service in September 1917 and later served in the newly-formed Royal Air Force. He served in Italy from November 1917 with 66 and 67 Wings. He was discharged in 1920.

9 – Harry Hayden Ellis was born in Stepney in 1878 and married Emma Frances Thornbury in 1903. In the 1911 census, he is listed as a journalist. During the war, he served in the 6th Battalion of the London Regiment as a rifleman. He died in 1951.

17 – Henry Emerson Sanderson, a bank clerk who had married in 1909, served in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. He survived the war, but died in 1931.

23 was the home of the Squires brothers, whom we have met before. Alfred Webb Squires was a clerk working for Nestlé before the war and joined Queen Victoria’s Rifles (1/9 Battalion, London Regiment) in August 1914, he went to France in November that year and served there until he was wounded at Gommecourt, where he was a stretcher-bearer during in the fighting on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. He was awarded the Military Medal, possibly for his actions that day. He spent the rest of the war in the UK and got married in 1918. His brother Sidney Charles Squires was already in the Royal Navy in 1914 and served as a sick-bay attendant through the war, on a variety of ships – including one that was involved in a minor way in the Battle of Jutland. Both Squires brothers survived the war.

25 – Their neighbour was Frederick John Bryan Lucas, born in 1874. He does not appear to have married and the other people at number 25 were Wilfred and Katie Kent, so perhaps he was a boarder or relative of theirs. He was commissioned into the Worcestershire Regiment in 1917 but was seconded to the East Yorkshire Regiment. He is listed in the electoral register as a Lieutenant in their 2/4th Battalion, which was then based in Bermuda.

27 – At the next house lived Frank Moorhouse, who lived there with his wife Julia and two children and was working as a traveller (i.e. travelling salesman) when he attested in the Derby Scheme in December 1915 aged 32. He attested the day after his younger child Geoffrey was born. In June 1916, he joined the Royal Garrison Artillery, before transferring to the Military Foot Police, with whom he served in France from May/June 1917 and became a Lance Corporal. He served on the Western Front from May 1917 until he was discharged from the army in September 1919.

Communication sent to Moorhouse in Arthurdon Road in late 1919

35 – Charles Bray served in the RAF, having joined the RFC in Jan 1916 when he was a student aged 18. He served as a wireless operator and was in France from May 1917 to March 1919, when he was demobilised.

49 – Frederick George Hunt was another RAF man. He was born in 1880 in Rotherhithe and worked as a clerk before joining the Royal Naval Air Service in April 1916. He doesn’t seem to have served abroad. In the electoral register, he is described as serving in Group 5, No 1 Area, RAF.

55 – Completing the odd side of the road is Reginald Thomas Wilding, who was born in Dulwich in 1898 and lived in New Cross in 1911. During the war, he served in the Ammunition Column for 57th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. He served in France from 4 October 1915. He survived the war and died in 1969.

Evens

12 – On the opposite side of the road William Francis Halfpenny is the first entry at number 12. He was born in 1883 in Walworth and worked as a carpenter and joiner before he joined the Royal Navy in September 1916. He served on a number of ships, including HMS Greenwich. In September 1917, he distinguished himself by his behaviour when HMS Contest was sunk (sadly, the details of his behaviour are not recorded). He was demobilised in early 1919. He died in Lewisham in 1954.

HMS Contest, torpedoed by German submarine U-106, 18 September 1917 ©IWM (Q 38536)

14 – The Halfpennys neighbours included George Sidney Bird and his parents George William and Sophia Emma Bird. George junior was born in a clerk, in 1911 he worked for the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich, but when he joined up in November 1915, he was working for St John’s School, Wellington Street, Woolwich – and the school promised to top up his army pay to the level of his civilian pay. Bird joined the Queen’s Westminster Rifles (16th Londons) on 10 November 1915; he was sent to the Western Front in June 1916 and joined the unit a week into the Battle of the Somme. A year later, Bird was wounded in the thigh and was away from the unit until early October. Soon after that, he was allowed home for ten days to get married to a Sydenham woman named Lilian on October 24th. He was in action again at the start of the German Spring Offensive in 1918 where he was badly gassed on 22 March, as a result of which he was sent back to England at the start of April and remained in the UK for the rest of the war. He was sent out to France again on 20 November but returned to be demobilised in January 1919.

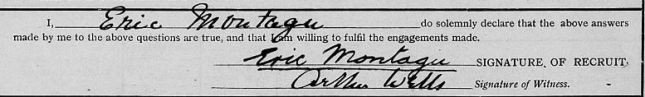

16 – The next household included two servicemen, the youngest of the seven children of Mary Rebecca Gooding and her late husband Charles: Horace Rason Gooding was born in 1889 and was a gas fitter; he served in the Army Service Corps – the register lists his unit as 3rd DMT (District Mounted Troops) Company. Thomas Edgar Gooding managed to serve in both the army and the navy. He was an 18 year old clerk at the Home and Colonial Stores when he signed up for the 21st London Regiment (First Surrey Rifles) in 1909. He remained in this territorial unit through to its mobilisation in 1914. In March 1915, he went to France with them and served out the rest of his contractual period in the battalion before being sent home in January 1916 and leaving the army the February. A year later, he joined the Royal Navy and served out the rest of the war on various ships including NHS Devonshire.

18 – There were three voters registered at number 18. Two were a couple Richard John Walsh and Elizabeth Martha Walsh, who had married in 1902 and had at least three children (three are listed on their census return for 1911). Richard was from Bermondsey and worked as a jewellery buyer for a general store in 1911; he served in the Royal Field Artillery as a gunner during the war. The third voter was Frank Ernest Lancaster, who was serving in the Royal Marines Light Infantry, having joined up in 1901. He was born in 1879 in Walthamstow and worked as a slater for Walthamstow Council, taking after his father who had the same job for London Country Council (Walthamstow was then in Essex). Quite why he ended up being being registered at the Walshes’ house – did he know them? Had to lived there at some point earlier in the war? I simply don’t know.

20 – William Albert B. Thornbury was another Arthurdon Road man serving in the London regiment. He was born in Forest Hill in 1898; in 1911 he was a schoolboy living in Honor Oak Park. During the war he joined the London Regiment – I don’t know when, but he was serving before 1917 and in 1918 was in the 6th Londons and ended up as a Corporal. He married Dora Brightwell in Sussex in 1926 and they had at least one child (a son, Hugh was born in 1931), but William died in 1936.

26 – Edward Richard Pettitt was a shipping clerk and enlisted in the London Regiment on 17 April 1917, having already registered with them before his 18th birthday. He later served in the Royal Engineers as a switchboard operator and was discharged in 1919, having served only in the UK.

28 – Herbert Thomas Barnes was born in November 1879 and worked as a “handicraft instructor” for London County Council. He lived at number 28 with his wife Ellen. He joined the Royal Naval Air Service on 2 June 1916 and was absorbed with it in into the RAF in 1918, with whom he served until his demobilisation in February 1919.

32 – Charles Edward Calnan was a Sergeant in the Royal Field Artillery, but I have not been able to find out any more information about his military service. There was a Charles Edward Calnan living in Rotherhithe in 1911, a shorthand typist born in the area in 1890, who died in 1977. Perhaps that was this Arthurdon Road man.

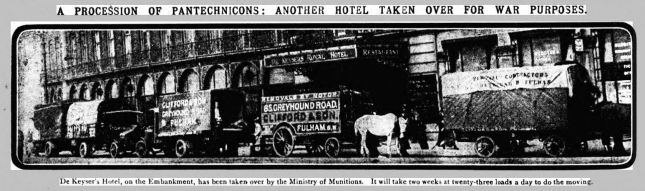

36 – Albert George Maxted (or Manstead) was a theatre manager in 1911. His war service is neatly summed up in the National Roll of the Great War: “He joined in February 1917, and in the following year went to France, where he was engaged with the Cinema Section of the RASC, entertaining the troops in the forward areas.” He ended up as a Sergeant and was discharged in February 1920. He lived another 50 years and died in September 1970.

38 – Lawrence Sydney Pudney was born near Sittingborne in Kent, but lived in South East London before the war. He was married to Marian Bowes in 1912 and was a teacher employed by London County Council when he enlisted in the Royal Engineers in 1916. He served in France for 9 months and left the army in 1919. He lived until 1978.

40 – Bookbinder’s overseer Richard Nathaniel Lamb and his wife Lilian were registered at number 40, with Richard absent in the RAF. Initially, though, he was an orderly working with the British Red Cross, having previously been a territorial member of the RAMC. He went to France in May 1915 and rose to the rank of sergeant-major, working at the Anglo-American Hospital at Wimereux. Then in July 1917 he applied for a commission in the Royal Flying Corps. He became an officer in November that year and served through to 1919 as a Lieutenant in the new Royal Air Force, but doesn’t appear to have gone out to the front with them.

R.N.Lamb’s service record, showing the name his house in Arthurdon Road went by in 1918: “Inverkeithing”

44 – Another RAF man lived a few doors down: John Sinclair Jenkins, a civil servant from Peckham who had joined the RNAS as a carpenter in November 1915 aged 29, served in France from June 1916 and by 1918 was a Corporal, serving with number 217 Squadron RAF.

48 – Frederick Kitchenmaster served as a Sergeant in the 4th (Ross Highland) Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders. He was killed in action on 21 March 1918, the first day of the last great German Offensive on the Western Front. He is commemorated on the Arras Memorial, meaning that he has no known grave; given that this was months before the register was compiled, one must assume that his family did not know of his fate in the summer of 1918 – months after his death.

A gas sentry of the 4th (Ross Highland) Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders, Frederick Kitchenmaster’s unit, at Wancourt, 23 October 1917. ©IWM (Q 6132)

52 – Harry George Kennedy appears to have served twice. Originally a private in the 20th London Regiment (Blackheath and Woolwich Battalion), having enlisted on 3 September 1915 he served on the Western Front for exactly six months in 1915. He then suffered from elipeptic fits, which had happened before the war. He was discharged in December 1915, but seems to have rejoined and served in the Labour Corps. On the electoral register he is listed as serving in the Officers’ Mess, 16th Corps HQ.

54 – Victor Robert Stotesbury was born in Greenwich in 1888 and grew up in Deptford; before the war he was a house decorator. He served as a gunner in 189th Siege Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery and survived the war. He lived until 1979.

60 – Percy Edward George Farrow is listed as a corporal in a Royal Engineers Anti-Aircraft unit (service no 563779), but I have not been able to find any more information about his military career. He appears to have been a library assistant, who was born in Chelsea in 1880 and died in 1968.

68 – Walter Herbert Victor Badger was born in 1883 and in 1911 lived in Ladywell, on Wearside Road, working as a gas company’s representative traveller. In 1916, giving his occupation as “outdoor inspector” he joined the RNAS, later becoming an RAF aircraftman, serving in Kingsnorth, Kent (the airfield was where the power station is now), as a fitter.

As with any attempt to list service personnel from a particular place, the list is imperfect. For one thing, the names were provided by the head of the household, potentially meaning that men who had moved away before the war were listed because they had no other address even if they had left home already. For example, both Youngs brothers gave addresses on Whitehorse Lane, South Norwood in their files at the end of the war.

In addition, those men who were reported missing but who had died or whose deaths had not yet been reported would have been listed (like Sgt Kitchenmaster). On the other hand, men who had already been discharged or died were not listed as absent voters, so it is far from a full list.

The service dates of those whose information I have been able to uncover may suggest that there were some others who joined up earlier but died or were discharged. Three were already serving before the war (one of them as a part-time Territorial soldier), two joined up in 1914, three in 1915, seven in 1916 and five in 1917. Overall there was a broadly-even split in recruiting between those who joined the Army between August 1914 and December 1914 (as volunteers) and those who were called up in 1916-1918, having attested under the Derby Scheme or been conscripted. In this record of Arthurdon Road, those joining up in 1916-17 far outnumber those from 1914-15. This suggests either that the street was quite unusual in its pattern of enlistment, or that earlier recruits had been killed or discharged – or possibly both. Unfortunately, it is hard to identify which young men living in Arthurdon Road had died or been discharged before the summer of 1918.

One of the war dead associated with Arthurdon Road was Sydney William Batchelor – the only entry on the CWGC database with the street listed in his details. He enlisted in Chelsea and served in the Royal Army Medical Corps. He died of wounds in 1918 while serving with the 1st/3rd (North Midland) Field Ambulance, and was buried in a cemetery at Etaples. His parents are listed by CWGC as living at 48 Arthurdon Road, possibly meaning that between the summer of 1918 and the return of the Commission’s information form, Nellie Kitchenmaster had moved out and Mr and Mrs Batchelor had moved in.

It is not a complete list, but hopefully this blog post gives some sense of the range of things that Londoners did during the war. And this is only among the military roles that men played, and it doesn’t include the service or work undertaken by women.

Nonetheless we can see that, at the point in time that their service was registered in 1918:

- Eight served in the RAF and/or its predecessor units (RFC and RNAS);

- Five served in the Royal Navy or Royal Marines (excluding RNAS);

- Four served in the London Regiment;

- Four served in the Royal Artillery (RFA and RGA);

- Three served in the Royal Engineers;

- Two served in the Army Service Corps;And the other others served in other infantry units, the Military Police and the Labour Corps.

Arthurdon Road was probably no different to other roads in the area, or many other areas of the country. There was no dominant industry that kept men out of the forces – or pushed them into it through unemployment. Men from Arthurdon Road served around the world – but primarily on the Western Front or at sea. Among them were heroes, decorated for their bravery. I hope that by highlighting some of their stories, I have shown some of the variety of experiences Londoners had in the armed forces during the Great War.